Garnish with Lemon: Finding the Story through Objects & Edits in “Ways to Prepare White Perch”

Jennifer Genest illustrates revising and editing in her actual draft of her award-winning story, Ways to Prepare White Perch.

BY JENNIFER GENEST

Objects are a writer’s friend. Almost any object is loaded if you think about it long enough. I am always surprised when objects in a story end up doing the “heavy lifting (explaining difficult or emotional things)” without it seeming forced or obvious.

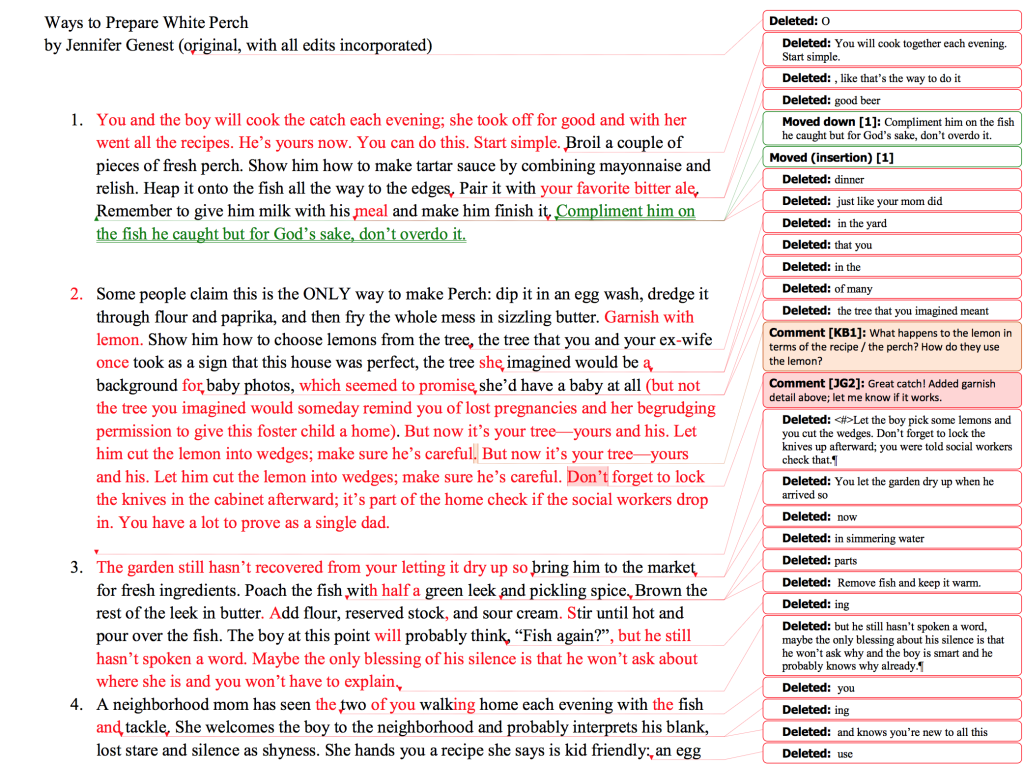

My flash fiction piece written at the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop, “Ways to Prepare White Perch,” won the 2014 Ryan R. Gibbs Award for Short Fiction by New Delta Review and received an honorable mention in the Kenyon Review Short Fiction Contest. The marked-up original copy of “Ways to Prepare White Perch” illustrates how the story changed over the course of about five versions. Every edit—some from my writing group, some from a teacher, and some from the New Delta Review editor—helped me find the heart of the story.

What’s the “top” story here? A man goes fishing each day and cooks the catch with his new son. The recipes offered opportunities to dip down into the “bottom” story, which is loss and grief. Here are a few objects and edits that did some of the heavy lifting:

- The lemon tree. To me, a lemon tree in a yard represents pure domestic harmony, and at the same time, the lemon is sour. The lemon tree here dips into the bottom story—joy and hope for a couple buying a new home, but paired with the pain of miscarriage. The lemon tree evolves, though, and gives way to another working object: the knives (which then feed in information about who this boy is and what is at stake). In the final draft, the New Delta Review editor suggested I be more specific about how the lemon was used in the recipe—and so three words “Garnish with lemon” became the new, more natural connector between top and bottom story.

- The boat. In the fourth version, I realized they went fishing on a boat. A childhood memory helped me out—one summer, my brothers wanted to name their small row boat and put its name on the stern using vinyl decals; my father, ever-conservative and anti-bumper-sticker, tried to discourage them. So, this found object did the heaviest lifting for me.

- The beginning and the ending: The original first paragraph had this as the second line: “She took off for good and he’s yours now.”

Here’s what my friend Nancy Zafris had to offer about that line: “This is entirely bottom story. It’s like the author stepping in to give us the info we need. What if you said something like this: ‘She took off for good and with it went all her recipes.’ That leads right to the next point, which is to start out simply with cooking the perch.”

Nancy’s suggestion was excellent; the story felt so much more balanced with just that single edit. If you ever have the opportunity to be Nancy’s student, listen to her.

The original version ends with an image—the boy’s eyes. But an image wasn’t the most powerful way to close. Closing with the father’s feelings—hunger, sadness, joy, hope—was what the story really needed.

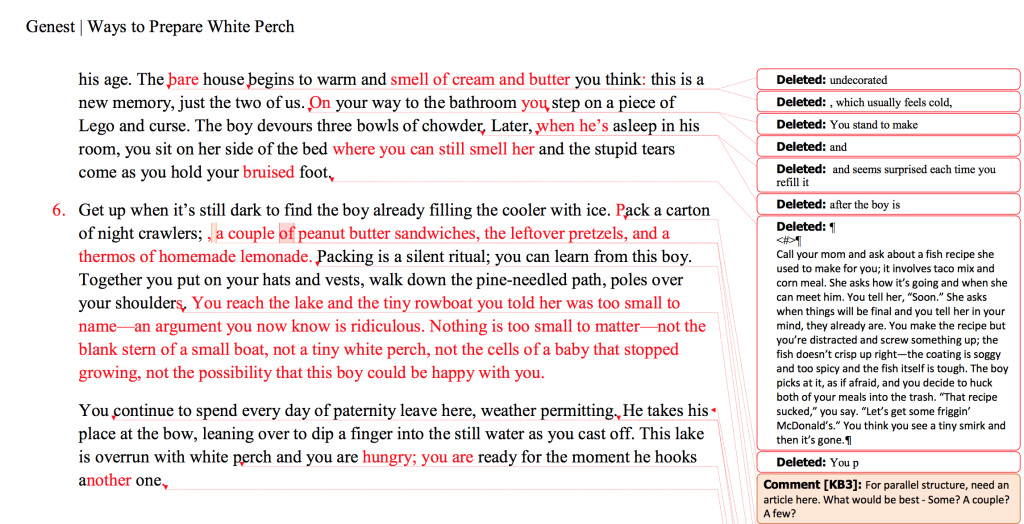

Line edits throughout were instrumental; I was so grateful for the help and suggestions of friends with fresh eyes to help me with that. The Lego paragraph had the most sensory detail and the most line edits. Even though it was not the ending paragraph, to me it felt the most resonant. Having your child take three helpings of something you cooked feels like a reward to me, a message that you are finally doing something right as a parent—even if it’s just one small thing.

******

On Revision is a column by writers on revising and editing and includes a showcase of the author’s annotated drafts. The contributors discussed the selected work on an episode of Behind the Prose.

******

Jennifer Genest grew up riding horses and playing in the woods of Sanford, a mill town in southern Maine. She has a MFA (Antioch University Los Angeles) in creative writing and was a Peter Taylor Fellow for the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop. Her writing has appeared in Paris Play, Cactus Heart, The Doctor TJ Eckleburg Review, and New Delta Review.